|

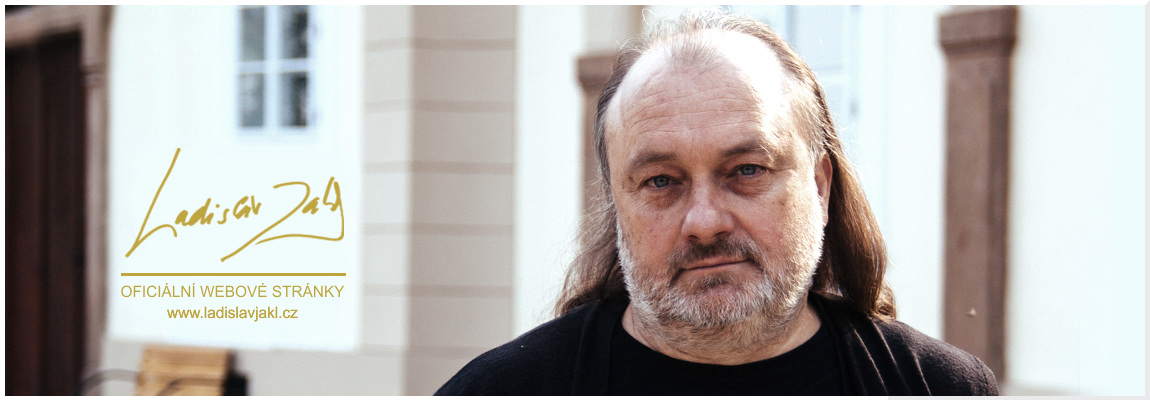

CIVIL SOCIETY – INNOCENT BEAST

Publikováno 07.03.2012 v kategorii: Publikované články

Václav Klaus skirmishes with his opponents on several fronts. One of those on which all is definitely not quiet is the perennial dispute on the intellectual concept of “civil society”. Although this debate has been raging for years, few subjects have given rise to such confusion as civil society.

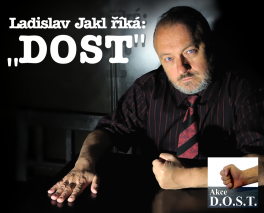

Who are Klaus’s critics in this fight? I will divide them into two groups. The first views Václav Klaus’s concerns about the civil society project as an example of his intolerance of spontaneity of any kind, or as a manifestation of statism, which does not tolerate activity uncontrolled by the state. The second group is well aware of the point of Klaus’s objections, but does everything it can for the first group to be as large as possible. For this second group, the model of civil society is a tool to promote its influence and power outside democratic or market principles. Because it does not want to be unmasked in its efforts, it brands Klaus’s criticism of its practices as the suppression of ordinary, more or less idealistic, social activities. Therefore, the chaos surrounding the interpretation of the term “civil society” is not a sign that concepts have been poorly defined, but the result of long-term systematic propaganda intended to win over the activists of societies, foundations, public benefit corporations and civic associations by giving them the impression that Klaus is threatening their freedom to engage in all sorts of activities. The model of civil society is not another term for the spontaneous activities of the people or for diverse manifestations of the life of society. That would be a fundamental mistake. A free open, vibrant society is a natural platform for numerous activities, whether or not they are organized. These activities are intended to satisfy the needs of their participants or to promote the goals that these participants consider to be priorities within society. Such initiatives unnecessarily feel aggrieved when they hear that the model of civil society is a threat to human freedom. Klaus’s words of caution about civil society are not trained on their idealistic and perhaps highly utilitarian activities, but on ideology according to which “outdated” democracy needs to be replaced by other principles and in which a network of non-state structures plays the role of an instrument of power. Some of these structures become pressure groups which can be quite brash about enforcing their priorities. They have it easy in a democracy because they exploit the phenomenon of concentrated and diffuse interest. This phenomenon forms the basis of all lobbying and makes the promotion of group interests over the interests of the wider public all the more effective. Many decisions exist where the damage is evenly distributed, so it is not felt so hard by those affected and does not motivate them to defend themselves effectively, while the results of such decisions benefit a small group where every member is highly motivated and the team is often well organized. Special-interest groups are inventive in spreading propaganda designed to portray their fractional interests as a public interest. However, all these manifestations are part and parcel of life in a free society and attempting to eradicate them would be foolish. Yes, sometimes these forms of coercion reach a point where they need to be addressed in order to protect diffuse interests, but, again, this is possible only by exerting competitive influence and wielding decisive, solid reasoning; it is impossible institutionally. So far, we have discussed only instruments of influence. Yet extreme manifestations of “civil society” want more than influence. They long for power. We can see this in professional chambers with compulsory membership which, by law, are delegated a part of state administration. They act like authoritative state bodies towards their members and have the power to prevent outsiders from entering the market. Thus a special-interest group with no universal mandate is able to take decisions on citizens and their rights. Another example is the establishment of rules on collective bargaining, according to which the agreements concluded by trade unions are also valid for workplaces where no unions exist. It could be said, then, that the working conditions of one employee are determined not by the law or a contract, but by the decisions of employees at a completely different company. Another example is where professional associations or special-interest groups delegate or nominate candidates to bodies which are entrusted with state administration (such as media councils). In this respect, a member of such a group could be said to be taking decisions for fellow citizens who are not members of any such group. Another example is administrative decisions where the parties to the proceedings include, by law, specific special-interest groups (e.g. the organizations of environmental activists and radicals), whose members thus hold more decision-making powers than public institutions elected by citizens. On an international level, these are pressure groups and special-interest organizations which – largely financed with money distributed by public institutions – are given rights similar to those of interstate organizations with a mandate. It would be wrong to blame anyone for the fact that special-interest groups consistently pursue their own agenda. This is normal in a free society. The problem is not the activities of special-interest interest groups, trade unions, chambers or “non-profit” organizations. These entities are merely striving to maximize their profits within set conditions. The problem lies in the rules that delegate these entities certain powers. These rules are the product of post-democratic ideology. The axis of this ideology is the concept of “civil society”. At first glance, it is just a name, and we might join with Shakespeare in saying: What’s in a name? That which we call free society by any other name would smell just as sweet. It could be argued that civil society can be viewed as free society, structured by spontaneously arising organizations. But that is not the case. The very term “civil society” contains a certain coloured vision of the world. Each of us plays many roles. In the morning, we get up and greet members of our family as a father, a sister, or perhaps even an uncle. We commute to work as passengers. At work, we are the colleagues of our colleagues. After that, we might be a concert-goer, or perhaps a diner in a restaurant. Some roles overlap and are combined, others alternate. Being a human is not a role. It is an identity. But being a citizen is a role. We are a citizen when we come into contact with the state, a municipality, or any other government apparatus. A citizen is a person as a voter, a taxpayer, a benefit recipient, as a subject of regulation. It is a broad, but not overarching, role. It is not an identity. Civil society is therefore primarily a society of citizens defined by human roles, not of people with all that that entails. It is a society viewing man more narrowly, just as a citizen. Civil society cannot serve as an umbrella term for the whole of the human community, but only for a defined type of activities and relationships. It does not draw on all of human solidarity. If we were to admit that man is a citizen in all his roles, we would meet the definition of a totalitarian society. In such a society, the state aspires to encroach “totally” into all areas of human life; indeed, this is how the system got its name. In a sense, the concept of “civil society” could be viewed as a community living in a state that is consistently derived from the will and mandate of citizens, unlike a totalitarian regime, where the citizen is just a cog in the state machine. Yet, according to this concept, it is not a society in the true sense, nor a mutual social community, but a structure, a state, an instrument of collective decision-making, and thus a form (albeit the most civilized) of violence against the freedom of individuality. In this concept of civil society, although the state supposedly exists for the citizen, as opposed to a totalitarian regime, where the citizen is only part of the whole and his identity is subordinate to the higher identity of the collective, in both cases we are still talking about the state and the relationship between the state and the individual, rather than relations between individuals or the spontaneous structures they have freely shaped between them. In parallel to the democratic state, there are various other communities with their own natural ties, natural non-intrusive and informal authorities, and even parallel systems with autonomous rules, rituals and institutional mechanisms. These form the core of public, non-intimate human existence. Anyone who has these parallel structures in mind when they use the term civil society is not only making a semantic error, but is also revealing their understanding of human solidarity. They are trying to transfer citizen-state relationship models to all other activities, including spontaneous and natural actions. At first glance, it seems to be inverted that post-democrats refer to civil society as a competitor to the state, an alternative which could crowd the state out of its domains and assume some of its functions. In reality, another factor is at play. Apparent pressure on the “civilization” of the state actually causes the state and its attributes to seep into areas for which they were not created. This seepage is more dangerous than state expansion per se. It is less noticeable and reduces our freedom no more conspicuously than state power. When the state is expanded, the borders remain distinct; the same does not hold true for seepage. Typical followers of the concept of civil society thus defined are betrayed by simple statements. At one conference, I heard that a reduction in state subsidies for non-profit organizations would be a direct threat to civil society. If anyone claims that civil society is merely a term for independent spontaneous and organized activity, how it is possible that these activities should be entitled to money forcefully collected by the state from taxpayers? How can these supposedly independent, spontaneous and natural activities be threatened by a lack of money from the state? The absence of money from the state could only undermine a quasi-state structure. A structure connected to the state, living off the state and allowing itself to be used by the state. In other words, an extended arm of state power. Followers of the ideology of civil society can also be recognized by typical sentences in the vein of: “Why should the state do it when this or that public benefit organization can do it instead?” Or perhaps: “We need to fill the empty space between the state and the individual; only closet statists want the state to govern isolated individuals and thus have a firmer grip on power.” The borderline triteness of these sentences reveals that the speaker either does not understand or even purposefully obscures the principle of the state as a platform for the establishment and performance (and enforcement) of collective decision-making. Talk of the “space between the citizen and the state” is typical for the ideology of civil society. Its supporters accuse opponents of wanting to keep this space a vacuum. Democrats, for their part, often unnecessarily counter that they do not want a vacuum, but also want to fill this space with the spontaneous activities of the people. However, this defensive stance adopts the post-democratic tenet that such a space BETWEEN automatically exists and should exist, and that the dispute is simply about how it is to be filled and with what. Yet there should be no space between the citizen and his state. A particular emphasis should be placed on the key word HIS. Defenders of the cliché about the space between the citizen and the state do not see the state as an institution belonging to citizens, but as a monster that must be somehow circumvented, replaced, outdone by another model of collective decision-making. By civil society. So they do not feel the need or necessity for citizens to be able to affect their state directly. Their vision is based on the idea that the state (and politics in general) was set up by some kind of paratroopers from other worlds. Therefore, they see sense in parallel structures replacing democracy by taking over a direct share in decision-making, or in viewing pressure groups as an intermediary between the citizen and the state. These organizations are meant to function as a filter, a monopoly intermediary. As a sort of “key holder”. A citizen who is separated from the state by some kind of “live” space loses the possibility of directly mandating the state and continuously updating and reviewing that mandate. He becomes dependent on corporatist structures. Followers of this ideology do not view the state as an institution standing and falling with the mandate of its citizens, but as a separate creature. However, it is a fundamental right of the citizen not to be separated by the state by any barrier. He is entitled not to have any translator from Czech to Czech, any intermediary, between him and the state. The citizen is entitled to manage and control the state directly, and not to be separated from his state by a broad-backed entity seeking to obtain the sovereign right to interpret his wishes and interests. Space for spontaneous organized activity by the people should exist and should be infinitely large, but is not associated with, and is entirely independent of, the link between the state and the citizen. Another catchphrase of those advocating the model of civil society is that certain structures should perform certain activities for the state, instead of the state, because this is purportedly better and more efficient. If anyone is to do something for the state (instead of the state), then, first and foremost, they are admitting that they are touching on domains primarily within the realm of the state. They just borrow them, with various “alternative structures”, from the state supposedly in order to improve efficiency. They also claim that these functions would be performed better by non-governmental organizations than the state apparatus, but because they are doing this “for the state” they demand advantages from the state. At the same time, the state retains control of these “loaned” activities. The protagonists of the model of civil society thus admit that this is an activity which, in principle, does not belong to the sphere of individual decision-making. Along with this admission, they are saying that the state is not an ideal place for collective decision-making (i.e. decisions imposed on individuals). Their goal is to take over from the state (and the sphere of democratic control) not only a certain amount of care or a range of activities, but also the right to manage public goods, receive state resources in return and assume the authority to make decisions concerning other people. And that is dangerous. If the state, though democratic, is a form of violence, the blade of this violence must be kept in the rigid sheath of democratic institutions which have been mandated and are limited by democratic norms and public control. If the state treasury seeps out of democratic control while retaining the possibility to interfere in people’s lives and take their money, etc., this is the most dangerous form of statism. We should not want someone else to act for the state. We should want the state to do as little as possible, but to do the little that it does on its own. Only the state can act for the state. If someone else acts in the name of the state, this “replacement” entity will have the power to use violence against citizens, but its subordination to democratic and control mechanisms will be lost. Public goods, the management and use of which may warrant the imposition of collectivist violence, should be managed and used under the democratic control of a democratic state, because otherwise there is no other authority for its existence. If thousands of spontaneously arising social activities are geared towards giving advantages to oneself and one’s surroundings, then this is not activity “for the state”, but for oneself, of one’s own will, and for one’s own needs. We cannot tacitly assume that the state is initially the sole legitimate operator of such activities and that spontaneous action is only an alternative (and sometimes better) secondary solution. Spontaneous authentic actions must be initiated independently of the public sector, otherwise there can be no talk of spontaneity and authenticity. Anyone wanting to prevent or restrict such spontaneous actions would be committing an attack on freedom. However, there is no chance, nor has there ever been, that anyone of Václav Klaus’s ilk criticizing the model of civil society would act in this way. Yes, the promoters of “civil society” consider themselves to be under attack when a government subsidy is reduced or refused, or if their claims to tax concessions are challenged. A subsidy constitutes at least the direct involuntary participation of taxpayers in the funding of a certain activity, whereas selective tax relief is the same involuntary participation, but indirect, hidden, and therefore does not require democratic promotion in competition with other priorities. The obligation to pay for public goods on behalf of those entities enjoying selective relief is passed on to other taxpayers. The tendency to give organizations and groups power over the people and to operate instead of the state, or even to control the state, must be viewed as a form of corporatism. Corporatism itself arose out of frustration with democracy and the inability to address this frustration within the system. A typical example of this thinking is the sentence: We are fed up with the self-centred bickering of politicians. These words, which would not be out of place in a Mussolini speech or Hitler’s Mein Kampf, actually come from a classic Czech text on civil society – the founding statement of the Impuls 99 movement. This is nothing less than a direct attack on democracy. If the authors had wanted to remain within the bounds of democracy, they would have targeted their indignation at specific politicians and parties, and they could have criticized them, rightly or wrongly, as brutally as they liked, and could have claimed that they would make a better job of politics, or they would have delegated someone they trusted. The sentence cited above, though, condemns politics as a system and politicians as a “class”. If the authors, in their own words, are fed up with the “bickering of politicians”, or legitimate competition among people who had received a mandate from their free fellow citizens in free elections, they cannot be pursuing anything less than the dismantling of the system and the introduction of something other than democracy. And in the meantime they will try to bypass the democratic system with other methods not based on a mandate from citizens arising from free and fair elections. Civil society is presented as an innocent model against which only those with malevolent intentions could protest, when in fact it is a beast gnawing away at our freedom bit by bit. Václav Klaus noticed this, which is why he is portrayed as a fiend incarnate by activists advocating the model of civil society. Ladislav Jakl from Today’s World and Václav Klaus (Festschrift In Honour Of Václav Klaus President of the Czech Republic) Fragment, Prague 2011 |

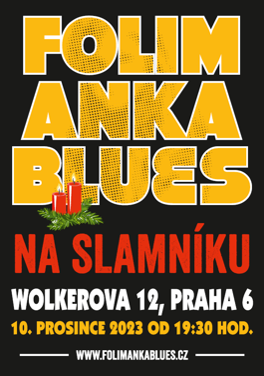

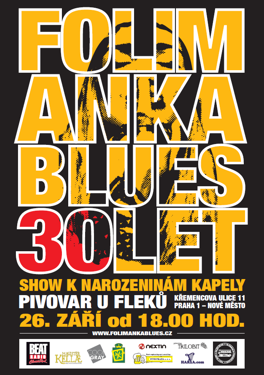

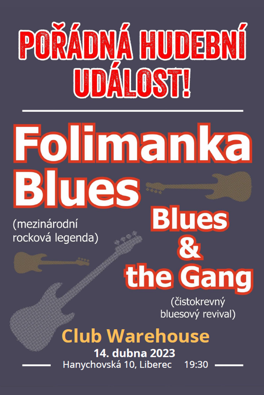

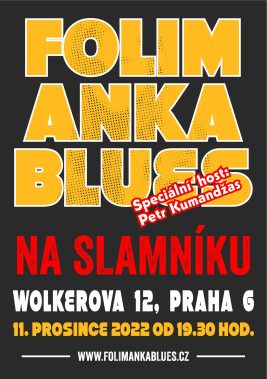

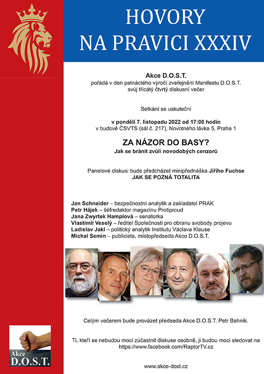

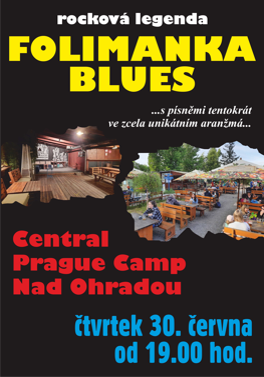

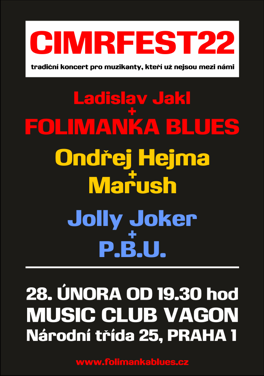

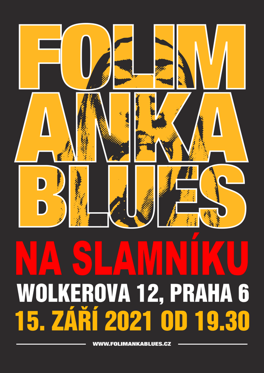

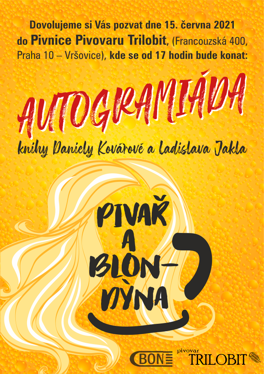

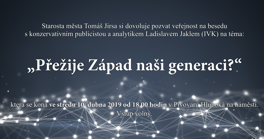

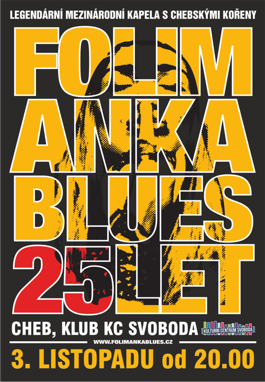

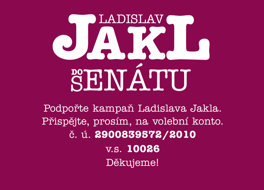

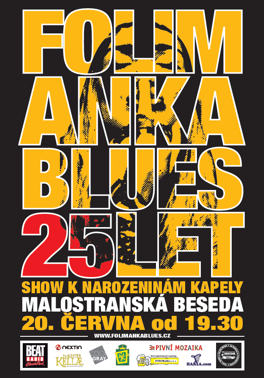

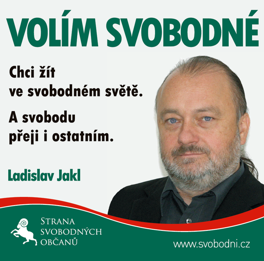

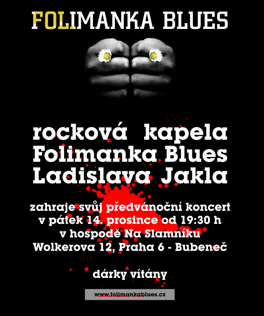

17. 12. 2024, 19.30 – Na Slamníku, Bubeneč: koncert rockové kapely Folimanka Blues 20. 11. 2024, 19.00 – Pivovar Nestville, Hniezdne, Slovensko, česko-slovenské Superfinále První pivní extraligy 14. 11. 2024, 11.00 – Společenský sál hotelu U Zeleného stromu v areálu pivovaru Zlatá Kráva v Nepomuku, L. J. moderuje Slavnostní vyhlášení cen Sdružení přátel piva 08. 11. 2024, 18.00 – Pivovar Hendrych, Vrchlabí, L. J. v porotě degustační soutěže pro pivovarské domovarníky 19. 10. 2024, 09.30 – Břevnovský klášter, L. J. v mezinárodní porotě pivní degustační soutěže Golden Bohemia 12. 10. 2024, 09.00 – Hotel Samechov, Chocerady: L. J. moderuje konferenci SOSP Konzervativní kontrarevoluce 09. 10. 2024, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, finále patnáctého ročníku degustace českých ležáků První pivní extraligy 25. 09. 2024, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, druhé semifinále patnáctého ročníku degustací První pivní extraligy 21. 09. 2024 – Nostalgická myš, Kokořín – Šemanovice: koncert kapely Folimanka Blues 11. 09. 2024, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, první semifinále patnáctého ročníku degustace První pivní extraligy 08. 08. 2024, 19.22 – Modrá vopice, Vysočany: L. J., zahraje v rámci večera Open Mike, věnovaného Kaštánkovi 31. 07. 2024, 18.00 – L. J. hostem v pořadu Nepodvolení televize Protiproud 29. 07. 2024, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, ochutnávka nealkoholických piv v rámci vložené degustace První pivní extraligy 01. 07. 2024, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, degustace asijských továrních ležáků v rámci vložené degustace První pivní extraligy 26. 06. 2024, 11.00 – Prima CNN: L. J. živě v debatě o česko-slovenských vztazích 19. 06. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, degustace slovenských továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 15. 06. 2024, 19.30, Na slamníku, Bubeneč: koncert L. J. s kapelou Folimanka Blues 26. 05. 2024, 19.00, Vinyl Club, Klatovská třída, Plzeň: koncert L. J. s kapelou Folimanka Blues 11. 05. 2024, 10.00 – Pivovar Na Rychtě, Ústí nad Labem, L. J., v degustační porotě soutěže Ústeckého pivního jarmarku 10. 05. 2024, 14.00 – Pivovar Na Rychtě, Ústí nad Labem, L. J., v degustační porotě soutěže Piva Ústeckého kraje 07. 05. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, páté kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 25. 04. 2024, 18.00 – Radio Prostor, L. J. hostem pořadu Prostor pro dva M. Stoniše 24. 04. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, čtvrté kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 20. 04. 2024, 12.00 – Výstaviště Zahrada Čech, Litoměřice, L. J. na Mezinárodním pivním festivalu a vyhlášení soutěže Zlatá pivní pečeť 09. 04. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, třetí kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 06. 04. 2024, 12.00 – Zámek Litomyšl, L. J., v porotě degustace národní soutěže Litomyšlský korbel 26. 3. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, druhé kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 25. 3. 2024, 13.00, Křižíkovy pavilony, Výstaviště Praga – Holešovice: L. J. v diskusi na téma „Kam se poděla tradiční česká hospoda a kam se budou pivní podniky a kultura pití piva dále ubírat“ v rámci Prague Bar Show 22. 03. 2024, 18.00 – Pivovarský dvůr, Zvíkovské Podhradí: L. J. v porotě degustační soutěže Jarní cena českých sládků 18. 03. 2024, 12.00 – Pivovar Velké Březno: L. J. předává ocenění za vítězství ležáku Březňák za vítězství ve 14. ročníku degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy. 14. 03. 2024, 10.00 – Rozhovor L. J. pro blog Tomáše Lukavce Zákony bohatství na YouTube 12. 3. 2024, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, první kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2024 11. 03. 2024, 18.00 – Rozhovor L. J. pro Rádio Xaver na téma „Média“ 28. 02. 2024, 19.30, Vagon, Národní třída: L. J. s kapelou Folimanka Blues vystoupí na Cimrfestu, koncertě pro muzikanty, kteří už nejsou mezi námi 22. 02. 2024, 14.00, Rádio Prostor: rozhovor L. J. Markétou Šichtařovou v pořadu Prostor pro dva 01. 02. 2024, 11.00, Pivovar Regent, Třeboň – L. J. předává pivovaru Regent cenu za vítězství zdejšího ležáku v degustační soutěži Česko-slovenské Superfinále První pivní extraligy 30. 12. 2023, 16.00, Kbelský pivovar – L. J. předává Kbelskému pivovaru cenu za vítězství zdejšího ležáku v degustační soutěži První pivní extraligy Král Prahy 22. 12. 2023, 17.00 – L. J. živě v TV Protiproud v pořadu Jistě, pane tajemníku 10. 12. 2023, 19.30, Na slamníku, Praha-Bubeneč: Předvánoční koncert rockové kapely Folimanka Blues 08. 12. 2023, 17.00, Strahovský klášter sv. Norberta: L. J. na vyhlašování vítězů mezinárodní degustační soutěže piv Golden Bohemia 03. 12. 2023, 19.00, divadlo SEMAFOR, Dejvice: L. J. „křtí“ nové klipy sboru Gospel Time Suzany Stirské 24. 11. 2023, 10.50, Ostrov: beseda L. J. se studenty ostrovského gymnasia 22. 11. 2023, 19.30, Svätá Barborka, Banská Štiavnica: Česko-slovenské superfinále První pivní extraligy 19. 11. 12.00, kulturní dům Kladno-Sítná: L. J. v porotě největší soutěže kapel hrajících naživo Skutečná liga 17. 11. 2023, 22.00, ČT24: L. J. hostem pořadu Události, komentáře na téma výročí 17. listopadu 1989 16. 11. 2023, 18.00, UOL Klub, Praha 5 – Přednáška L. J. na téma Největším ohrožením naší prosperity…jsme my sami https://www.uolklub.cz/uol_event/listopad-2023/ 15. 11. 2023, 17.00, Grand Hotel International – Představení knihy IVK Sebedestrukce Západu: Pád zrychluje https://www.institutvk.cz/akce/predstaveni-knihy-sebedestrukce-zapadu-20-pad-zrychluje.html 11. 11. 2023, 14.00, První Pivní Tramway – Král Prahy: degustace První pivní extraligy všech mikropivovarských ležáků vyráběných na území na území hlavního města 09. 11. 2023, 10.00, Rodinný pivovar Bernard, Humpolec – L. J. moderuje slavnostní předávání Výročních cen Sdružení přátel piva 21. 10. 2023, 14.00 – L. J. po devětadvacáté účastníkem Memoriálu Matěje Kuděje 19. 10. 2023, 17.00 – L. J. v živě vysílaném rozhovoru s Petrem Hájkem na TV Protiproud 14. 10. 2023, 10.00 – Břevnovský klášter, L. J. v porotě mezinárodní degustační soutěže Golden Bohemia 11. 10. 2023, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, finálová degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 30. 09. 2023, 18.30, Balbínova poetická hospůdka, Vinohrady: afterparty na počest třiceti let trvání rockové kapely Folimanka Blues 26. 09. 2023, 18.00, Pivovar U Fleků, Nové Město: večer na počest třiceti let trvání rockové kapely Folimanka Blues 12. 9. 2023, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, druhé semifinále degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 11. 09. 2023, 19.55 – L. J. hostem živě vysílaného pořadu Aby bylo jasno s moderátorkou Kateřinou Dostálovou 29. 8. 2023, 19.30 – První Pivní Tramway, první semifinále degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 29. 08. 2023, 17.00 – L. J. natáčí pořad X talk s Lubošem Xaverem Veselým 14. 08. 2023, 10.00: hotel Rabbit, Trhový Štěpánov – přednáška L. J. na téma „Pohled na potravinovou bezpečnost a politiku Fialovy vlády“ na půdě platformy KLUB 2019 12. 07. 2023, 18.00 – L. J. v pořadu Jistě, pane tajemníku na TV Protiproud 23. 06. 2023, 19.45, Pizza Micio, Plešivec, Slovensko: koncert L. J. s rockovou kapelou Folimanka Blues 31. 05. 2023, 09.30: CNN Prima News – L. J. živě o přijet eura a o situaci v EU 25. 05. 2023, 19.00: L. J. hostem živě vysílaného rozhovoru na Radiu Xaver 12. – 13. 05. 2023, Ústí nad Labem, Kostelní náměstí: L. J. v porotě degustační soutěže Pivo Ústeckého kraje 05. 05. 2023, 16.00, TV Kolektif: L. J. v pořadu Debatní klub diskutuje s ekonomem Kovandou o vyhlídkách českého hospodářství 02. 05. 2023, 16.00, TV Protiproud: L. J. živě v pořadu Hovory s nepodvolenými – Jistě, pane tajemníku 01. 05. 2023, 15.00, Památník Vítkov: L. J. svým projevem zahajuje shromáždění podporovatelů iniciativy Zachraňme náš stát 25. 4. 2023, 20.00 – První Pivní Tramway, páté základní kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 22. 04. 2023, 15.30, Výstaviště Zahrada Čech, Litoměřice: L. J. s rockovou kapelou Folimanka Blues v rámci programu Mezinárodního pivního festivalu 15. 04. 2023, 19.30, Hi-Fi klub, Plzeň: L. J. s rockovou kapelou Folimanka Blues 14. 04. 2023, 19.00 – Warehouse, Liberec – L. J. s rockovou kapelou Folimanka Blues 11. 4. 2023, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, čtvrté kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 28. 3. 2023, 20.00 – První Pivní Tramway, třetí kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 25. 3. 2023, 18.00 – Pivovarský dům Zvíkov, L. J. v degustační komisi a na vyhlašování Jarní ceny českých sládků 23. 3. 2023, 17.00 – Protiproud TV: L. J., živě v pořadu Hovory s nepodvolenými 16. 3. 2023, 14.00 – Pivovar Uhříněves, L. J. předává ocenění za vítězství ležáku Alois v soutěži První pivní extraligy o nejlepší ležák z pražských pivovarů Král Prahy 15. 3. 2023, 20.00 – První Pivní Tramway, druhé kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 06. 3. 2023, 9.30 – Poslanecká sněmovna, vystoupení L. J. na semináři „Manželství pro všechny a Istanbulská úmluva“ 01. 3. 2023, 19.00 – První Pivní Tramway, první kolo degustace českých továrních ležáků První pivní extraligy pro rok 2023 28. 02. 2023, 19.30 – Vagon, Praha – Národní třída: L. J. s kapelou Folimanka Blues na Cimrfestu – koncertě pro muzikanty, kteří už nejsou mezi námi 07. 02. 2023, 19.30 – Jazz Rock Cafe, Plzeň: L. J. kmotrem knihy Jaroslava Pompa Rok hlupců 02. 02. 2023, 11.00 – pivovar Zubr, Přerov: L. J. předává vedení pivovaru Zubr cenu na vítězství v česko-slovenském Superfinále První pivní extraligy |